Hydropower has been a strategic good to drive the economy toward prosperity in the context of Nepal, which has a huge potential to harness this renewable energy to accelerate its economic growth. It has also been sought as a means to check the import of petroleum products to check, in turn, the widening trade deficit, the main problem that the country faces at present as it struggles to reduce pressure on the depleting foreign currency reserves.

According to the Department of Electricity Development (DoED), Nepal’s total electricity production capacity has reached 2,150 MW through 129 projects, each of which has the capacity to produce more than 1 MW. Of the amount, the private sector’s contribution is 1,452 MW. In the past one year of Nepali calendar 2078 BS alone, a total of 710 MW was added to the national grid, which however, is below the government projection to produce over 1,000 MW during the period.

As it has many more hydropower projects in the pipeline, Nepal has been looking forward to selling its energy to the neighboring countries, India and Bangladesh. Provided the targeted goal is achieved, the landlocked country can accelerate its economic growth by using its hydropower that could lead to a rapid industrialization and a notable growth in job opportunities.

Although Nepal’s prospect of exporting electricity to India is often put into question mainly due to the unpredictable policies introduced by the southern neighbor time and again, the excess production still is in favor of the landlocked country. Reduction in the cost of production caused by the smooth supply of power could help industries of various scales and sizes to flourish. This could help improve the competitiveness of the local products in the global market, paving the way for the country to earn more foreign currencies from international trade.

Government statistics show that the domestic demand for electricity is growing at the rate of 10 percent annually. This has lured both local and foreign investors to inject additional investment into this sector. In addition to this, the government has planned to increase per capita consumption of electricity to 700 units by 2022/23 from less than 200 units at present. Given the high potential it has in terms of generating revenue, almost all the local governments have put harnessing hydro potential to their highest priority.

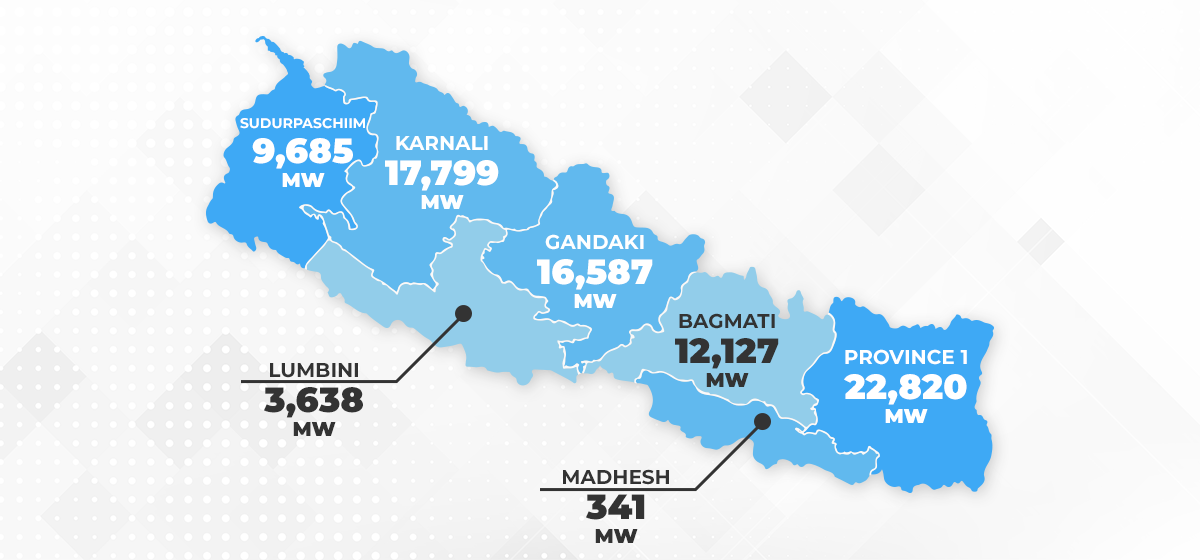

Province-wise distribution of hydropower potential

With the country embracing a federal system of governance some five years ago, there is a growing call for the decentralization of its economic resources among the sub-national governments as well. Federalism can yield good outcomes only if these sub-national governments are economically self-reliant.

Gyanendra LalPradhan, chairman of the Energy Development Council at the Confederation of Nepalese Industries, says Nepal has the potential to decentralize hydropower at the local level. According to him, the income from selling energy could provide the provinces with resources to fund their own development projects. “Developing hydropower can help replace high-value raw materials and energy imports, and allow gross value addition, compared to the investment in other sectors,” he argues.

A study report of the Water and Energy Commission Secretariat unveiled in 2016 shows that Province 1 has the largest potential to produce hydropower energy in Nepal. Mechi, Kankai, Koshi and Kamala River are the main sources of electricity production in the province. Madhesh Province on the other hand has the least potential among all. Bakaiya, Bagmati, Kamala and Koshi are the rivers that can be used to produce electricity in this province.

| Province | Potential (in MW) |

| 1 | 22,820 |

| Madhesh | 341 |

| Bagmati | 12,127 |

| Gandaki | 16,587 |

| Lumbini | 3,638 |

| Karnali | 17,799 |

| Sudurpaschim | 9,685 |

Of the country’s total capacity to produce 83,000 MW, half of the potential is considered economically viable. Four major rivers Koshi, Gandaki, Karnali and Mahakali and their tributaries have enriched the sub-national levels with the sound hydropower potential.Available statistics shows that six provinces, except for Madhesh Province in the southern plain area in the country, have enormous capacity to develop hydropower to generate downstream benefits. The low-cost electricity can be used to increase agricultural output, boost tourism and generate employment, among others.

| Major River Basins | Economic Potential | |

| Project Sites | Megawatts | |

| Koshi | 40 | 10,860 |

| Gandaki | 12 | 5,270 |

| Karnali and Mahakali | 9 | 25,125 |

| Southern Rivers | 5 | 878 |

| Total | 66 | 42,133 |

Source: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (2011)

Apart from the construction of big projects, decentralized energy systems have numerous advantages over mega energy projects. Some of the main advantages include environmental friendliness, lower upfront costs, greater affordability and reliability, lower risks, an easier ability to cope with system failures, and community empowerment. Despite these advantages, the type of governance used while constructing these systems can still play an important role in yielding these positive impacts to local communities. Experts suggest taking all these factors into consideration while developing these systems in order to benefit the local population.

Energy consumption at provincial level

According to NEA records, Bagmati Province occupies the top spot on the energy consumption index, and the revenue generated from electricity consumption in the province is also the largest of all the seven provinces. Bagmati is followed by Lumbini and Madhesh provinces on the index.

Despite immense potential, Karnali Province lags far behind in terms of utilizing its hydro potential. Studies have shown that Karnali Province alone has the potential to generate 17,799 MW of electricity, but the energy consumption rate is the lowest in the province. Similarly, the NEA’s revenue from the province, just Rs 480 million, is the least among the seven provinces. It shows that the province has a lot of hydropower potential untapped that can help uplift its large section of population from extreme poverty.

| Provinces | Energy Sales (MWH) | Revenue (in billion RS) |

| Province 1 | 1,041,635 | 10.87 |

| Madhesh | 1,254,188 | 16.07 |

| Bagmati | 2,113,215 | 24.93 |

| Gandaki | 428,554 | 4.39 |

| Lumbini | 1,301,342 | 15.45 |

| Karnali | 46,525 | 0.480 |

| Sudurpaschim | 235,303 | 2.09 |

Source: NEA (2020)

Besides individual investors, the federal government, too, attaches high priority to utilizing the unutilized hydro resources of mainly Lumbini Province, Karnali Province and Sudurpaschim Province. With the effort of the government, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and European Investment Bank (EIB) are providing amounts equivalent to USD 112.3 million and Euro 100 million, respectively, as concessional loan to NEA for the electrification of these provinces. Similarly, Asian Development Bank (ADB) has also provided an amount equivalent to USD 200 million as concessional loan for the development of power transmission and distribution system strengthening under SASEC. Under this project, Nepal is expected to receive a Norwegian grant amount of USD 35 million as committed by the Government of Norway.

Challenges

According to an ADB report entitled ‘Hydropower Development and Economic Growth in Nepal 2020’ the underperforming electricity sector in Nepal, with inadequate and unreliable supply of poor-quality electricity, is the major development constraint. “Though the situation has been improving, even today the basic energy needs of Nepali citizens are only being met partially,” reads the report.

As of 2019, about 89 percent of the population had access to electricity, but the supply was of poor quality and unreliable. Despite the dramatic increase in per capita electricity consumption, from 63 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per annum in 2000 to 177 kWh per annum in 2018, it remains among the lowest in the world; Nepal’s per capita electricity consumption is one-twentieth of the global average, according to the ADB report.

Providing electricity access to remote areas is one of the foremost challenges of any developing country. Nepal is no exception to this. As such, Nepal's remote areas suffer either from limited or no access to electricity. Apart from production, national grid expansion is a must among other decentralized energy options.

Experts say that big renewable energy projects can fail under a decentralized system as they lack certain types of governance. According to Surya Kumar Sapkota, an expert of the energy sector, renewable energy projects in Nepal have been designed using a polycentric approach to governance. However, the donors in most of the foreign investment projects remotely control the project process, thereby hampering the intended polycentric governance strategy, which is originally conceived to include multi-level stakeholders.

Polycentric governance is a more contemporary mode of governance used for social energy projects and has multiple decision-making centers, each of which operates with some degree of autonomy. Polycentric energy governance involves multiple scales (local, regional, national, and global), mechanisms (centralized command and control regulations, decentralized and local policies, and the free market), and stakeholders (government institutions, corporate and business firms, civil society, individuals, and households). It is useful mostly when implemented with principles, such as equitable distribution of power, multiple actor decision-making, and discretionary implementation.

Way forward

A number of studies made in this field have suggested that decentralized energy systems could be the most suitable alternatives for both short-run and long-run options. The options should be technically and financially assessed for the selection between off-grid electrification and grid expansion. In Nepal, micro-hydropower (MHP), solar photovoltaic, diesel generators and backup systems have been identified as major and viable forms of off-grid technologies that can be used for energy access. The government has prioritized off-grid energy technologies in its development plans. As a result, off-grid technologies are now widespread in Nepal. As of the last fiscal year (2021), a total of 3,000 MHP projects contributing 35 MW of electricity have been installed. More than 600,000 household-level solar PV systems with battery-backup systems and 1,500 units of institutional solar PV plants have already been installed.

To increase electricity access, not only relevant electricity policies need to be formulated, but also significant sectoral policy and institutional reforms are required. In addition, the upgradation of transmission lines and substations is required to help the provinces evacuate the electricity produced at the local level along with improving the supply system from other regions. By the end of 2019/20, the total length of transmission line has reached 4,269.7 circuit km, which comprises of 1.3 km long (8 No of Towers) 132 kV double circuit from GIS to Trishuli-3B hub, 38.6 km long (120 No of Towers) 220 kV Double circuit from Trishuli-3B hub to BaadBhanjyang and 4.8 km long (14 No of towers) 220kV four circuit from Badbhanjyang to Matatirtha, Kathmandu. In addition, about 1.35 km length of a 220 kV four-circuit underground cable route leading to the Matatirtha Substation has also been constructed, shows the NEA annual report.

The transmission system provides an important link between the power generated from various power plants being owned by NEA, independent power producers and distribution networks ensuring reliable and quality power to be supplied to the consumers. Keeping in view of the role of transmission lines, the state-owned power utility has established a separate Transmission Directorate that has been delegated the responsibility to plan, develop, implement, construct, operate, maintain and monitor high-voltage transmission lines and substations from 66 kV to 400 kV voltage level. These are some of the good beginnings in regard to tapping the untapped hydro potential. It is high time the government bodies concerned put in place decentralized energy systems to adequately harness the hydro potential that Nepal offers in abundance.