Amidst the challenges posed by climate change and the imperative for sustainable development, Nepal stands at a critical crossroads in its quest for cleaner cooking solutions. The Government of Nepal has articulated an ambitious objective within its second Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target, to ensure at least 25% of the population is using electric cooking (e-cooking) by 2030. This target assumes critical significance for Nepal, where the majority of households still rely on traditional biomass for cooking, thereby engendering notable health, environmental, and societal ramifications. The recent census data, as of 2078, underscores the prevailing situation, with a mere 0.53% of Nepalese households embracing e-cooking, thereby accentuating the substantial chasm separating the present state from the envisioned future. To realize the stipulated 25% target, Nepal confronts the imperative of augmenting e-cooking adoption by an order of magnitude nearly 50-fold within the next six years. Foremost among the requisite infrastructural prerequisites is the assurance of reliable access to electricity. Absent a steadfast and pervasive electrical grid, the transition to e-cooking remains a distant aspiration. The availability of dependable electricity is indispensable for fostering the wide-scale acceptance of e-cooking solutions, facilitating households in transitioning away from conventional biomass fuels towards cooking solutions that are both sustainable and conducive to human health.

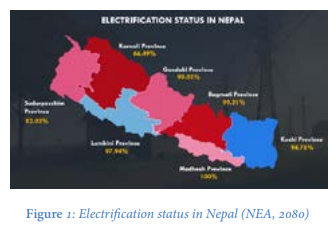

Nepal has made notable progress in expanding its electrical infrastructure, achieving an electrification rate of 95.03%.

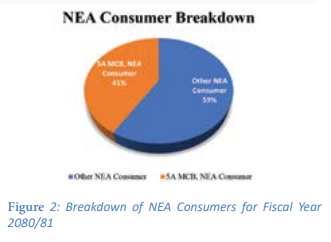

As of the fiscal year 2079/80, NEA had 5,134,058 customers, marking a 7.72% increase from the previous year. Among these consumers, a significant proportion approximately 41.32% or 2,121,371 domestic consumers possess a connection capacity of 5 Ampere (A) Miniature Circuit Breaker (MCB) only.

This low-capacity connection could, however, potentially impede the widespread adoption of e-cooking solutions. 5A meter could take up to 1150 Watts (at 230 Volts) size e-cooking stove. Meanwhile, a typical e-cook stove, in general, has approximately 2000 Watts of power capacity. Hence, an upgrade to a 15A size is recommended for optimal performance. Such an enhancement ensures an ample power supply, thereby augmenting the efficiency and effectiveness of the e-cook stove, while offering a more reliable cooking experience. Addressing the needs of these consumers will be essential to ensure they have access to the necessary electrical infrastructure and support to transition to cleaner cooking methods. But what does the market data reveal about the demand for e-cooking appliances?

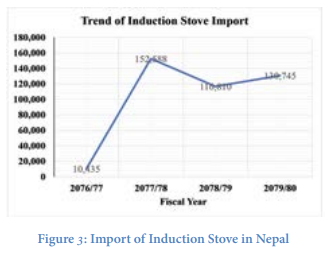

The import data demonstrates a remarkable trend in the demand for induction cooktops. Beginning in 2076/77 with a modest import of 10,435 units, the subsequent years witnessed an exponential surge in import, indicative of a growing preference for this eco-friendly cooking technology. Notably, in 2077/78, the import of induction stoves skyrockets to 152,588 units, marking a staggering increase from the previous year. However, from 2077/78 to 2078/79, there is a slight decrease in imports, indicating a possible stabilization or saturation of the market. From 2078/79 to 2079/80, there’s another increase, although not as dramatic as the initial surge. Simultaneously, the data highlights a burgeoning interest in infrared cooktops, albeit on a smaller scale than that compared with induction stoves.

Furthermore, the customs data of the fiscal year 2080/2081 reveals that the import duty rate for induction stoves is merely 1%, regardless of whether they are imported from SAARC countries or from another third country. This low import duty rate is likely aimed at making e-cooking stoves more affordable and promoting their adoption as a clean cooking solution in Nepal. Given this trend, it is crucial to assess the comparative costs with traditional LPG to understand the economic benefits for households.

Adoption of e-cooking in urban areas is relatively more feasible and economically viable compared to LPG. A comprehensive cost analysis comparing these two cooking methods illuminates significant potential savings for households switching to electric cooking. Though urban households are equipped with higher electrical load capacities and MCB ratings, than their rural counterparts, most of them still rely on LPG for cooking.

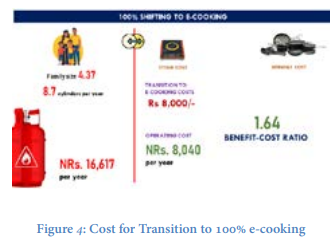

Transitioning to e-cooking entails an initial investment of approximately NPR 8,000 for households with a 15A MCB, covering the purchase of e-cookstove and associated with cooking utensils. However, households with a 5A MCB would have to invest an additional NPR 2,000 for wiring and MCB upgrades, totaling NPR 10,000. Considering an average family size of 4.37 members, urban households typically consume 8.70 units of LPG cylinders annually, amounting to a yearly expense of NPR 16,617- with each cylinder costing NPR 1,910.

By opting for e-cooking, the annual operating cost was reduced to NPR 8,040, resulting in savings of NPR 8,577 per year with a Benefit-Cost ratio of 1.64. For households with a 15A MCB, excluding wiring upgrades, the initial investment of NPR 16,040 covers appliances and additional energy consumption, offsetting within 11 months through these savings, rendering e-cooking a financially viable option.

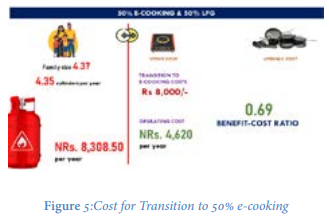

However, ensuring a reliable power supply, even in urban areas, is still a big challenge for Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA). Hence, using e-cooking, alongside LPG as a backup option, would be ideal. In a 50/50 hybrid scenario, where both e-cookstove and LPG are used evenly, the annual cost for a household would be NPR 20,929. This includes the fixed cost for appliances of NPR 8,000, the cost of LPG cylinders for 50% usage at NPR 8,309, and additional electricity consumption of 360 kWh costing NPR 4,620. Benefit-Cost ratio for this scenario is 0.69. The payback period for the initial NPR 8,000 investment is only 22 months, making e-cooking an economically viable option for urban households when combined with LPG.

The cost analysis demonstrates that transitioning to e-cooking is not only environmentally friendly but also economically beneficial. Lower operating costs and a relatively a short payback period for the initial investment make e-cooking an attractive option. As more households adopt e-cooking, it will contribute to reducing the reliance on LPG, decreasing household expenses, and promoting a cleaner and more sustainable cooking solution.

Nevertheless, despite all the cons, traditional biomass cooking still dominates the Nepali Kitchen, raising significant health concerns. Currently, more than 60 percent of Nepal’s population relies on traditional solid bio-fuels for daily cooking. Because traditional fuels do not burn efficiently, they produce excessive smoke along with countless toxic particles and harmful chemicals, putting everyone in the kitchen at risk. Consequently, there is an increased likelihood of respiratory, heart, chest, and lung diseases. According to a study by the World Health Organization, approximately 22,800 Nepalese die annually in Nepal due to smoke-related diseases.

Transitioning to e-cooking not only promises to mitigate the devastating effects of indoor air pollution on public health, but also holds the potential to reduce deforestation, empower women, and contribute to Nepal’s overall sustainable development goals. However, achieving this target and ensuring that no one is left behind requires addressing multiple challenges, including affordability, reliability of electricity supply, awareness, and behavior change. Particularly for the disadvantaged groups, with minimal electricity consumption, transitioning to e-cooking poses significant challenges.

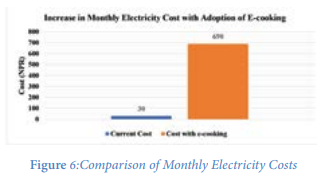

For 5A households consuming less than 20 units of electricity per month, NEA currently requires them to pay only Rs 30 as a monthly fee. If they were to use an e-cooking stove and consume an average of 2 units of electricity daily, their monthly consumption could easily exceed 60 units. This would place them in a higher tariff bracket, requiring them to pay NPR 690 per month, which represents a substantial increase of 20 times more than what they were previously paying. Hence, these households would be reluctant to switch to e-cooking.

Although firewood can be collected freely, there are significant opportunity costs associated with its use, including the time spent collecting it and health related issues. Women in these households spend hours gathering firewood, which could have been dedicated to other productive activities. Additionally, indoor air pollution caused by burning firewood poses health risks to the household members. While the financial return from using e-cooking may be negative, there could still be economic benefits if the time saved from not collecting firewood is used for paid employment or other income generating activities. However, this assumption of finding paid work may not be always true, as related job opportunities could be limited. And again, the switching cost, including wiring upgrades, and purchasing a stove and utensils (approximately Rs 10,000 per household), may pose a significant barrier. Banks may not be interested in providing loans for such small amounts. Microfinance institutions (MFIs) and cooperatives could serve this segment, but their interest rates are relatively high. Hence, incentivizing and offering subsidized financing options is imperative to facilitate the adoption of e-cooking among such households, enabling them to overcome initial costs and embrace cleaner cooking solutions.

Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC) has been undertaking various initiatives to promote clean cooking solutions in Nepal. One notable project by AEPC is a $49.2 million Green Climate Fund (GCF) project in clean cooking solutions. This project targets distributing 500,000 electric stoves (e-cookstoves), 490,000 Tier 3+ improved cookstoves (ICS), and 10,000 biogas plants in 150 local governments, spread over 22 districts of Terai. This project alone will provide e-cooking access to 7% of the entire population.

Similarly, AEPC, through the National Rural and Renewable Energy Programme (NREP), has established a Sustainable Energy Challenge Fund (SECF) to provide capital grants and interest subsidies on renewable energy technologies (RETs), including e-cooking solutions. Microfinance institutions and cooperatives are already leveraging this fund to offer subsidized interest rates to their clients/members, facilitating the adoption of e-cooking solutions.

While SECF’s interest subsidy may alleviate financial barriers, it may not still be sufficient for the Disadvantaged Groups (DAGs), consuming less than 20 units of electricity per month. To address this, the NEA would have to introduce a subsidized tariff structure for them to reduce their operating cost. To further support the adoption of e-cooking solutions among the DAGs, Local Governments (LGs) also need to develop targeted packages in collaboration with NEA and AEPC. Additionally, AEPC can explore revenue generation through the sale of carbon credits on the international market, leveraging the environmental benefits of e-cooking projects. The funds obtained from selling these carbon credits can be reinvested into providing grants for e-cooking initiatives, creating a sustainable funding cycle that promotes clean energy adoption and reduces the financial barriers for the most economically disadvantaged communities in Nepal.

GCF vs Carbon Market

Green Climate Fund was established in 2010, within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to assist developing countries with climate change adaptation and mitigation activities. The first GCF project was approved in 2015, and already four GCF projects have been approved for Nepal. Meanwhile, the Carbon Market has a little longer history UNFCCC’s Kyoto Protocol in 1997 formally opened the platform for emissions trading between countries with binding targets, through various market-based systems. One such initiative was the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which permitted a country with an emission reduction or limitation commitment to execute or finance a project in a developing nation. This project could then generate saleable certified emission reduction (CER) credits to help the country meet its Kyoto Protocol targets. Nepal registered its first CDM project in 2005, by AEPC.

GCF is indeed a good platform for countries like Nepal to access grants for clean cooking projects, however, it could be debated if it is a better option than Carbon Market, in terms of value for money. Furthermore, GCF project approval process is very lengthy, with a median line of 21 months, which could make the project itself redundant by the time of implementation!

For the GCF-funded clean cooking solutions project, of a total of USD 49.2 million, AEPC received only USD 21.12 million as a grant. However, by entering the carbon market and selling carbon offsets generated from the project, AEPC could have potentially earned even more revenue. If an e cooking stove could save 1.5 tons of CO2 emission annually, then the 500,000 electric stoves would save 3,750,000 tons of CO2 emission over 5 years. Though carbon credits from an e-cooking project can fetch up to $25 per credit for 7 years in the voluntary market, if we take a conservative value of the carbon credits at $20 per ton, for 5 years only, this could still earn $75 million from carbon revenue!

Thus, for e-cooking projects, Nepal can decrease reliance on grants by tapping into the carbon market. Carbon finance can make e-cooking more affordable for economically disadvantaged groups by monetizing offsets from its widespread adoption. This revenue can fund subsidies, lower tariff rates, and provide financial assistance, ensuring environmental and health benefits reach those most in need. This approach improves access to e-cooking while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing community welfare.

E-cooking holds great promise for environmental sustainability and public health, but it also presents significant challenges, particularly in making it affordable for disadvantaged groups. To ensure that no one is left behind, it is essential to implement targeted financial assistance, subsidies, and support mechanisms that address these economic challenges. This includes subsidized tariff structures, targeted financial assistance, and leveraging carbon finance to generate sustainable revenue. This integrated approach will facilitate the widespread adoption of e-cooking, directly contributing to Nepal’s sustainable development goals and fostering a cleaner, healthier future for all its citizens. It is imperative that we act now to ensure benefits to everyone out of these advancements!

The writers of this article are affiliated with Wind Power Nepal Pvt. Ltd. This article is taken from the 6th issue of urja khabar, a bi-annual magazine. Which was published on 15 june, 2024.