Energy Update

Rights of the Rivers of Nepal: A Concept

The philosophy of “Rights of Rivers”

The rivers have always been considered sacred by the Sanatan dharma that includes all the sects of Sanatan Dharma or Dhamma such as Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Vaishnavism, etc. All rivers are called “holy mother”, a place higher than the mother herself and therefore they have a special high place in the prayers as well as all religious rituals and practices. It is not possible to trace the date when this practice started but this must have started from a time when the homo sapiens of this region or the Aryans realised the importance of drinking water after every meal and this realisation must have increased with the discovery of agriculture which can be dated back to over 8,000 years in this continent.

This importance of river/water has been first included in the Rig Veda, the written form of which is estimated to be between 3,500 and 3,800 years old1 with its verbal practice continued from time immemorial, in Chapter3, 7 as well as in chapter 102,3,4,5. As the river Ganga and its tributaries in Nepal are referred to as “mother Ganga” in the Vedas and other ancient literature, it is obvious that the practice of worshipping water/river/spring source should have started even earlier than the first step in human civilization that started with the discovery of fire and continued through the domestication of wild animals over 10,000 years ago after the last glacial retreat. The discovery of Neolithic tools at the bank of Vishnumati River in Kathmandu and in Lubhu of Lalitpur also suggests the following three points:

• That the Neolithic tools were made and used by the hunter gatherers in the valley of Kathmandu.

• The hunter gatherer(s) were settled near the river for convenience of fetching water at the same time the river could have provided the hunter gatherer(s) a safer place to hunt the wild animals who appeared by the riverside at certain hour of the day relieving the hunter gatherer the trouble of finding a suitable hunt in the middle of the forest which could put him/them at higher risk.

• They must have started to understand the importance of fresh water for their lives. With this knowledge, the hunter gatherers should have been learning to take further steps into civilization that could have included washing, bathing and cattle rearing and grain harvesting. This must have led to the major change in their life style from a mobile one for hunting to a limited mobile one for cattle rearing to finally a fixed one required for grain harvesting.

Therefore, the concept of the right of the rivers has started with the human civilization that recognised the importance of rivers/spring sources/water as something most important for life sustainance and therefore all sources of fresh water were considered as sacred places prohibiting any kind of pollution of the water sources as well as water bodies. The whole concept of holy water bodies emerged with the fact of realisation that clean water bodies are important for healthy human lives.

Therefore, as the pioneers of the Rights of the Rivers philosophy as well as the concept that all should be happy quote “ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः, सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः । सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु, मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् । ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥ Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah, Sarve Santu Nir-Aamayaah, Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu, Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet, Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih” which means May All become Happy, May All be Free from Illness, May All See what is Auspicious, May no one Suffer, Om Peace, Peace, Peace” unquote who recognized the rights of everyone that can include all lives on earth or water to live, prosper and be happy, we should take the leading role in this movement which means practicing such rights and for that practicing to keep the living environment including the aquatic environment unpolluted and pristine not quite ignoring the fact that it all started with the fact that clean water is prerequisite for a healthy living of all the human beings. This notion has been extended to all living beings both flora and fauna in all environments including the blue water bodies both fresh and saline.

This philosophy and we, the followers of such philosophy, therefore, should practice the commitments to keep all the environments as pristine as possible duly recognizing the rights of every stakeholder without any discrimination whatsoever. This, therefore, includes the rights of the rivers of Nepal including all its stakeholders.

Rivers of Nepal

Nepal is home to approximately 6,000 rivers which together drain over 147,546 sq. km. of Nepal including the Kalapani and Limpiyadhura area claimed by India since the late fifties. All rivers of Nepal feed the Ganges either directly or being tributary of the larger rivers. The rivers of Nepal are classified as the first order rivers, second or lower order rivers based on their origin and flow. All rivers of Nepal are predominantly rain-fed.

However, the Nepalese rivers contribute about 70% of the total lean season flow and 47% of the total annual flow of Ganga at Farakka. The first order rivers of Nepal, the Koshi, the Gandaki and the Karnali are transboundary rivers that originate in China, cross the great Himalayas into Nepal and continue to flow into India feeding the Ganges. The Ganges flow into Bangladesh and to the sea at the Bay of Bengal. All these transboudary rivers are older than the Great Himalayas.

In between the first and the second order rivers often termed as marginalised rivers lies the Mahakali River which originates at the Limpiyadhura peak in Nepal. It has several names in Nepal and in India as Mahakali, Kali, Kuti Yangdi, Sarda, etc. The main tributaries include Kali Nadi (Kuti Yangdi meaning Kali Nadi in local language), Chamelia and Surniayagad from Nepal side and Darma, GoriGanga, DhouliGad from the Indian side. The entire length of the Mahakali River lies within Nepal even after 1816 when Nepal had to surrender to British India all Nepalese territories lying west of the River Kali6 and its reference as a border river is totally false: Nepal India border should lie along the western bank of the Mahakali River from its source at Limpiyadhura.

The first order rivers are fed by a large number of perennial as well as seasonal tributaries that originate at the great Himalayas, their glaciers and glacial lakes as well as spring sources in the hills and the mountains of Nepal and China. The second order rivers predominantly fed by monsoon precipitation in the rainy season and by the spring sources during the rest of the year originate in Nepal hills and feed the Ganges either independently or meeting the first order rivers on the way in India.

The third order rivers originate at the Siwaliks or at the foot of the Mahabharat hills and continue downstream meeting the higher order rivers. All of them are the tributaries of the Ganga except for the Mechi River which directly feeds the Mahananda River in India. Other lower order rivers originate at the Siwaliks as well as in the Tarai. Most of such rivers are live mostly in the monsoon.

| Main Rivers of Nepal | Basin Area in Nepal, sq. km. | %-age of area of Nepal | Mean annual flow at gauging station, BCM | Flow Index, MCM/sq.km. |

| Karnali | 41,058 | 27.83 | 42.164 | 1.03 |

| SaptaGandaki | 29,626 | 20.08 | 44.449 | 1.50 |

| SaptaKosi | 27,863 | 18.88 | 55.655 | 2.00 |

| Mahakali | 6,456 | 4.38 | 21.151 | 3.28 (1.42) |

| West Rapti | 5,150 | 3.49 | 3.88 | 0.75 |

| Babai | 3,000 | 2.03 | 2.74 | 0.91 |

| Bagmati | 2,700 | 1.83 | 4.32 | 1.60 |

| Kamala | 1,450 | 0.98 | 1.42 | 0.98 |

| Kankai | 1,148 | 0.78 | 1.89 | 0.98 |

| Total | 118,451 | 118,451 | 118,451 | 1.50 |

| Total Area of Nepal | 147,546 sq.km. |

It is evident from the above table that the largest river of Nepal in terms of total basin area in Nepal is the SaptaGandaki (called Gandak in India) River followed by the Karnali and the SaptaKoshi Rivers. In terms of the total annual flow, the largest river is the SaptaKoshi followed by SaptaGandaki and the Karnali Rivers. However, in terms of the flow index defined as the total volume of annual flow per unit area in square kilometres, the largest among the first order rivers is the SaptaKoshi followed by SaptaGandaki and the Karnali rivers, whereas the same for the second order rivers is Kankai closely followed by Bagmati and so on. The arithmetically largest flow index of Mahakali River is due to the fact that the total volume of flow of the river has been quoted as against the basin area in Nepal only though the actual flow index is 1.42 as presented herein in the parenthesis. As flow index is the number which actually defines the state of water availability in the basin on the one side and the same can indicate the extent of risk in terms of the water induced disasters, the index should be used with caution.

Origin of the Rivers of Nepal

The rivers of Nepal originated towards the later part of the Himalayan Orogeny that started about 50 million years ago. Therefore, all rivers of Nepal are younger than 50 million years. Geographically the first order rivers of Nepal cover all three regions, the Himalayas, the hills and the mountains and the Tarai whereas the second and the lower order rivers are located towards the south of the great Himalayas. As the Himalayan Orogeny moved in Nepal from north to south, the southern rivers of Nepal are generally younger than the northern and the trans-Himalayan rivers. The third order rivers that originate in the Siwaliks are mostly seasonal however some of them are perennial. Most of the perennial ones and some seasonal ones (with water underground) have been used for water supply and irrigation. But, only a few perennial ones are gauged. Therefore, no long-term data on the lower order rivers are available for study and discussion.

Similarly, are missing data on the spring sources even those spring sources which have been tapped for household water supply and irrigation since a considerable length of time. As mentioned hereinabove, all rivers of Nepal are predominantly rain fed. This includes snow and ice in the glaciers and high mountains, spring sources of the hills and the mountains and the ground water in the Tarai plains, all being predominantly rain fed. The spring sources yield most of the water in the monsoon season.

Most of this flow is the result of infiltration of rain water into the ground that may not even have reached the aquifer but could have fed the spring channel between the source and the spring itself. The quantity of ground water flowing from a spring source depends upon many factors that include, apart from the total quantity of rainfall in that particular monsoon, conditions of replenishment, connection between the ground water aquifer and the spring source as well as other conditions that either limit the rise of ground water level in the aquifer or conditions that support it.

The human factor that considers itself as the focal point of water use started its intervention in Nepal since about 30,000 years. This period coincides with the date of the most ancient human fossils in Nepal7,8 both near Danda River in Nabalpur9 and near Vishnumati River in Kathmandu.

Water availability in Nepal

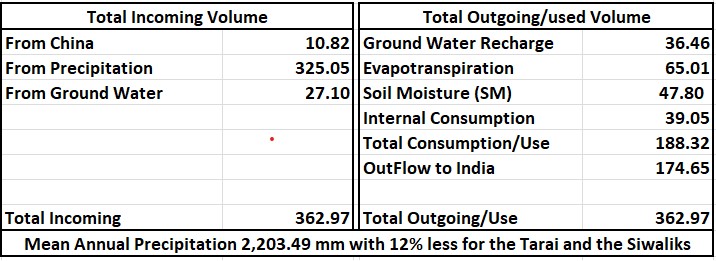

The total quantity of water available in Nepal from all the sources and their consumption as well as loss in billions of cubic meters (BCM) is as under10:

It is observed from above table that out of a total of 362.97 BCM of water flowing in Nepal annually, about 89.5percent is received directly from precipitation (including snow and ice melt, which cannot be reliably estimated) with the additional 27.10 BCM received indirectly through the spring sources in the lean season only (the ground water flow in the monsoon cannot be reliably estimated). Therefore, the total percentage of water flow in Nepal annually from precipitation is almost 97. This volume of annual precipitation is subjected to various losses that include ET, SM and loss on GW recharge, which amount to 149.27 BCM which is equal to 42.4percent of total annual precipitation. The remaining quantity of water is drained through numerous gullies, streams and the rivers and most of it crosses the border into India.

Consumption of Water in Nepal

The consumption of water linked closely to interventions in the rivers, spring sources and other sources of water in Nepal is governed by the priority of water use, a rule included in the Water Resources Act 2049 (1992). The existing policy on this priority is as under: Quote “While utilizing water resources following priority order shall, in general, be followed: (a) Drinking water and domestic users; (b) Irrigation; (c) Agricultural uses such as animal husbandry and fisheries; (d) Hydroelectricity; (e) Cottage Industry, industrial enterprises and mining uses, (f) Navigation; (g) Recreational uses; (h) Other uses” Unquote. A new bill has been tabled in the parliament for approval but the contents of the new bill with respect to the priority of water use have not meaningfully changed. Only changes incorporated are the order of water use within food production and inclusion of religious, traditional and environmental conservation as something of very low priority subject, which indicates a reverse attitude of the new bill11. Apart from the priority of water use as formulated in the above policy documents, the subject of water has been included in the rights and obligations of all three levels of the government often with overlapping rights and confusing obligations.

The main cause of such legal flaws is the fact that the bills were formulated and enacted after the elected representatives were already in office. Despite of all this, the water bodies of Nepal have been subjected to various consumptive and non-consumptive use in household supply, food and energy production as well as other industrial use. The priority for the social use of water has been the highest at the local level despite a lower priority in the policy documents of the government which only shows the government’s lack of understanding of the actual situation of water use in Nepal.

The major consumptive user of water in Nepal is the food production sector that mostly includes irrigation and animal husbandry followed distantly by household supply, sanitation as well as environmental conservation put together. It is estimated that about 3.98 BCM and about 7.97 BCM of surface water is being consumed in Nepal in the lean and the monsoon seasons respectively6. In addition to this, about 1.5 BCM and about 1.95 BCM of ground water has been respectively estimated to be used in the hills and the mountains and the Tarai annually. An estimated volume of about 6.85 BCM of ground water flows across the border to India unnoticed.

It is estimated that a total of 6,540 square kilometer of land that includes 4,340 sq. km in Tarai, 1,700 sq.km in the hills and 410 sq. km in the mountains is covered by surface irrigation using blue water12. This is only about 4.4 percent of the total area of Nepal though the total number of current river interventions may be very high because of relatively small command area of each of the schemes in the hills and the mountains due mainly to topographical reasons as well as reasons of water unavailability. The numbers vary from literature to literature though the total presently irrigated area is 14,332.87 sq. km. as per the white paper13. As far as household consumption of water in Nepal is concerned, no integrated numbers are available in the public domain however a value of 182.5 MCM has been calculated as the total annual water supply for household purpose on the basis of 100 liter of water consumption for each family of 6 per day. This number excludes the use of such water for any other consumption except for drinking, cooking, washing as well as other social use of water which is mostly carried out from public sources manually.

The largest non-consumptive user of water is hydro-electricity generation. The following table shows the number of river interventions, which does not indicate the percentage of water diverted for energy generation which is assumed to be 100 in the lean season.

Table on hydroelectricity14

| S.No | Stage of intervention | Total Number | Affected length of river, km | Total Capacity, MW |

| 1 | Under Operation | 107 | 481.50 | 1,247.50 |

| 2 | Under various stages of Construction | 234 | 1,053.00 | 7,349.70 |

| 3 | Under various stages of Application, Study, Design & Preparation | 282 | 1,269.00 | 17,869.60 |

| 4 | Other planned HP Interventions | 186 | 837.00 | |

| 5 | Mini, Micro or Pico under AEPC, GIZ or community HP | over 5000 | 1,500.00 | |

| Total | 5,140.50 | Km |

The most important element included in the above table is the total aggregate length of the river affected by the projects by way of water diversion from the natural river course to power generation water ways like canals, tunnels, conduits, etc. often leaving the downstream river course dry in the dry lean season. The estimated total length of such section is over 5,000 km. This affected length comprises a very high percentage of the total length of the perennial rivers that are subjected to such interventions mostly in the hills and the mountains. The percentage of such interventions is nothing in Tarai, very small in the high Himalayan valleys but practically completely occupied between the high Himalayas and the Siwalik foothills.

A number of water storage type interventions are under planning, some are under construction with the Kulekhani cascade of 106 MW in 3 stages in operation with annual regulation of water as just a hydropower project without any contingency for any other water use in the downstream areas. Additionally, the Government of Nepal, very interestingly, has been ignoring all other likely benefits of regulated water directly benefitting the users in India, who must have had access to additional 4 BCM of regulated water in the dry season in the last 40 years. Similarly, Storage type projects with annual regulation of water such as Budhi Gandaki (640-1200MW), West Seti (750MW) have been conceived as simple hydroelectric projects.

Similarly, there are a large number of similar river interventions for irrigation which are located all over the country including the Tarai but quite rare in the high Himalayan valleys. Similarly, a large number of valleys with perennial sources, mostly spring sources either at the source itself or downstream, have been tapped for household water supply, the impacts of which cannot be estimated as they are spread all over Nepal and that their numbers are incomparably large too.

As you move upstream from the river to its source areas, you realise that most of the rivers are fed by numerous creeks and brooks and counting interventions in each of such sources can be very tedious though their combined impacts on the river may be significantly high.

Status of E-flow, S-flow, H-flow

The dependence of river flow on spring sources especially for the spring fed rivers have been iterated both by the government and the civil society however, appropriate attention to these sources from the perspective of their safety, conservation, protection as well as management from the stakeholders especially from the government has not been seen. Similarly, are ignored the importance of the health of the spring sources in terms of water availability for household water supply, irrigation, hydroelectric generation, e-flow, s-flow, h-flows, etc.

E-flow that is understood to include all other riverine water requirements has been considered as 10% of the minimum monthly flow of the river without any rationale and river specific water requirements neither for ecological, environmental, social or other requirement of the river. Social requirement of water is of paramount value as cremations of human bodies are generally carried out by the side of a river and cremation requires free flowing river. E-flow requirement for projects within the protected areas as national parks, wildlife conservation areas, buffer zones, etc. is 50% of the minimum monthly flow and that too without any basis for such requirements. In addition, none of the requirements are followed in practice not even by the Government owned hydropower and Irrigation or other projects on rivers in the lean dry season when the river flow is the minimum.

Rights of Rivers in Nepal

As mentioned hereinabove, rivers and other sources of water and meeting points of two or more rivers have been considered as holy places by Sanatan Dharma and the same has been followed at the grass root level all over Nepal. However, this general principle has been grossly neglected by government policies and therefore, requirements to safeguard the rivers, riverine ecology and sources of rivers including the spring sources and wetlands has been missing in all the actions including permissions and licenses issued by the government to the developers of projects based on river interventions. Therefore, the government of Nepal should formulate plans, policies and actions that support conservation of all blue water bodies including the spring sources, rivers, lakes and other Ramsar areas for rationalising the use of water considering the fact that Nepal is a water stressed country with predominant stress of undersupply for over eight months followed by oversupply in the four monsoon months every year.

Rational use of water bodies should therefore honour the right of each and every stakeholder including the right of local communities living within the impact areas. Rational use of rivers should therefore include effective mitigation measures and should in no way be driven by a particular type of intervention. Such intervention maybe projects on water supply, food production, energy generation, navigation, etc. with or without periodic regulation of water including projects on flood water management as the storage of excess water in wetlands with or without water retaining structures, underground storage of water, etc. For countries like Nepal with tremendous imbalance in water availability in both spatial as well as temporal dimensions, intervention for regulation of water for flow augmentation should form one of the main agendas for the right of the rivers movement if such agenda helps support ecological or environmental conservation of the riverine stakeholders in the lean dry season. Provision of inland navigation seems to help support the rights of the rivers in its totality.

Storage of flood water with small dams in the Himalayan rivers sounds good but is questionable due to high siltation rate and consequent filling of such small storage areas much sooner than as calculated. The concept of “Interlinking of Rivers, ILR” proposed by Ramaswamy Iyer could have components that lie within the limits of rational use of rivers that support the riverine ecology but unfortunately the document, consisting of 17 chapters each authored by renowned experts on the field, prepared by a committee headed by Suresh Prabhu titled Interlinking of Rivers in India: Issues and Concerns, 2008 prepared with the aim of truly guiding the implementation of the ILR in line with the verdict of the Supreme Court of India, failed to justify the tax payers’ monies spent on its preparation as it made mockery of the ILR without actually saying so by not including the management aspect of the project as well as the committee’s concluding remarks leading to its implementation: in part, in full or its cancellation altogether.

Therefore, the rights of the rivers should be redefined to include “Rational Use of River Water” that guarantees that no one benefits at the cost of others: be it riverine ecosystem, the migratory communities including the migratory birds, the communities that live along the river and depend upon it and the entire stakeholders in the downstream areas. This means that the “rational use” of any water body including the rivers should be defined within a framework that can guarantee an unbiased coexistence of all the legitimate stakeholders with voice or without including the communities within and along the river, lake or any other water body irrespective of boundaries local, provincial, national or international.

Examples of extreme irrational use are the water damming structures on the Indian side of the Nepal India border which cause extensive export of floods during the monsoon to the communities on Nepal side due to such Illegitimate Indian interventions. Such demonstrations of enmity in the name of brotherhood should be stopped immediately for the benefit of communities on both sides of the border as well as for honouring the rights of the rivers and their legitimate stakeholders.

Mr. Pokharel associated with Nepal water conservation foundation (NWCF)

References

1 Maanavta.com

2Rig Veda, Internet Archive

3Rig Veda Sanhita, Internet Archive

4Edited by Dr. Umesh Puri Gyaneshwar, Charon Ved (in Hindi), Ranadhir Prakashan, Haridwar, India

5RigVedic Arya, 1956, Rahul Sanskritayan (check spelling!!), p-33-34

6.Compiled by: C. U. Aitchison B.C.S., Under-secretary to the government of India in the Foreign Department, Volume II, Calcutta 1892, A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries, Part III, Treaties, Engagements and Sanads Relating to Nepal No. LIV, pp 173-175 and memorandums pp.176-192

7.Janaklal Sharma, Hamro Samaj

8 .Banerjee N. R. 1969, Discovery of the Remains of Prehistoric Man in Nepal, Ancient Nepal, Journal of Department of Archeology, GON, No. 6, pp.51-55.

9.Banerjee N. R., J. L. Sharma 1969, Neolithic tools from Nepal and Sikkim, Ancient Nepal, Journal of Department of Archeology, GON, No. 9, pp.53-58.

10.Pokharel, G.S. and Gyawali, D. (2021, i.p. forthcoming). Estimating Nepal's Water Balance: Implications for Local, National and Transboundary Water Stress Management. Kathmandu: Nepal Water Conservation Foundation.

11. Water Resources Bill 2077

12 Santosh Nepal, Nilhari Neupane, Devesh Belbase, Vishnu Prasad Pandey & Aditi Mukherji (2019) Achieving water security in Nepal through unravelling the water-energy-agriculture nexus, International Journal of Water Resources development, DOI: 10.1080/07900627.2019.1694867, table 3

13. Minister Barsa Man Pun 2018 (2075BS), white paper on energy, water resources and irrigation published by GoN, Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation.

14. DOED website dated October 24, 2020

Conversation

- Info. Dept. Reg. No. : 254/073/74

- Telephone : +977-1-5321303

- Email : [email protected]