Energy Update

Electric two- and three-wheelers are everywhere in India

Indians living in lockdown as the Covid-19 pandemic rages cannot hear delivery boys’ motorcycles half the time: increasingly the two-wheelers are electric. In New Delhi, people can hear the ‘make India clean’ jingle as the rubbish collection van passes by, thanks to the van’s electric engine. In Kerala, schoolchildren awaiting their free lunch cannot hear the electric-powered food delivery vans. The electric vehicle revolution is almost a silent one.

When you leave a train station, you are likely to see two three-wheeler queues: one with electric vehicles, the other with internal combustion engines (ICE). Every day, the electric vehicle (EV) queue gets longer and the other shorter. India’s electric three-wheeler (E3W) fleet is the largest in the world.

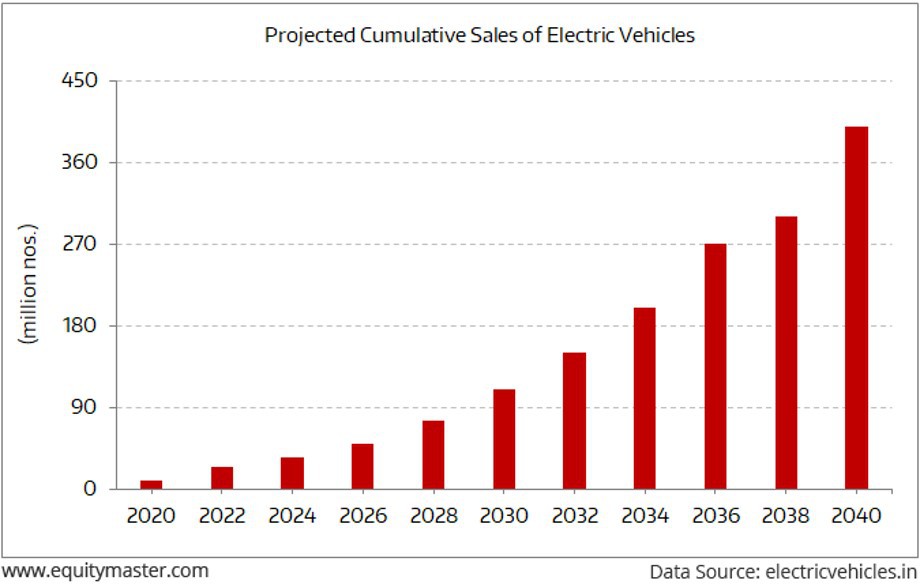

The scale of the shift to EVs could redefine several industries. Electric two-wheelers (E2W) have huge potential, especially with the world’s two largest manufacturers of two-wheelers being Indian. Almost all industry observers believe electric four-wheelers will remain a niche market for the next few years. In the large vehicle segment, it is electric bus fleets that are due to expand.

Electric two-wheelers have become an integral part of the supply chain of food aggregators, e-commerce firms, local transport and several other segments. Partly this is due to low taxes. The federal government reduced tax on EV purchases from 12% to 5% in July 2019; tax on ICE vehicles remains 28%. Several state governments have also done away with registration charges for EVs.

A new category is small electric bikes with a power capacity that is less than 100 cc ICE motorcycles. Electric bike startup Yulu has tied up with Delhi, Bengaluru and Mumbai metro train services so that electric bikes are available to hire in some stations.

Electric two-wheelers are still costlier than their ICE counterparts. Consumers do recoup the difference, as the charging cost is so much lower than petrol. High upfront costs, though, are holding up large-scale penetration of E2Ws in the individual market segment.

One hurdle is the low personal credit rating of many people wanting to buy E2Ws. Another is banks are not sure of the resale value of the vehicles. As a result, non-bank finance companies (NBFCs) have stepped in, with higher interest rates.

By most estimates, the size of the organised EV finance market in India will be INR 3.7 trillion (USD 50 billion) by 2030.

The changeover is expensive, and not just for individuals. A report by NITI Aayog, the government’s think-tank, estimates the cost of India’s EV transition at INR 19.7 trillion (USD 267 billion) over the years to 2030.

Some home-delivery companies are getting over the current problem by helping their employees buy or lease E2Ws.

Sulajja Firodia Motwani, the founder and chief executive of electric vehicle manufacturer Kinetic Green, says the price difference with ICE two-wheelers will largely disappear as E2W volumes pick up. That will lead to mass adoption.

“In India, two- and three-wheelers account for about 80% of total vehicles sold every year,” says Mahesh Babu, managing director and chief executive of Mahindra Electric Mobility. “These are promising EV segments going forward and expected to account for over four million units in next five to six years.”

“I think the tipping point for India will come from electric two-wheelers. I am hopeful that 2022 will be the tipping point for the industry,” says Amit Bhatt, executive director of integrated transport at World Resources Institute (WRI) India, a think-tank.

Electric three-wheelers (E3W), especially rickshaws, have taken over large parts of Indian roads without waiting for government policies. They are now the most ubiquitous means of transport for last-mile connectivity (the last leg of a journey from a transportation hub to a final destination). Several reports suggest that there are over 1.5 million such vehicles across India. More than 10,000 are added to the fleet every month.

Almost all E3Ws use lead-acid batteries. These are cheap and are easy to replace, eliminating the wait time for recharging. “The time required for swapping batteries is the same as that needed for refuelling ICE vehicles. That is why battery swapping has come up as a viable alternative,” Motwani of Kinetic Green says.

Big companies are looking to E3Ws with lithium-ion batteries – which would mean higher prices. It is unclear how much this would impact demand. Currently, such high-end E3Ws and small four-wheelers with lithium-ion batteries are the vehicles of choice by institutional buyers such as municipalities.

State governments and municipal bodies are driving the demand for electric buses. Ten state governments have electric mobility policies in place, while another half a dozen are finalising their policies. The federal government only recognises buses with lithium-ion batteries and fast charging capacity as e-buses.

Ashok Leyland, an Indian auto manufacturer, launched buses powered by lead-acid batteries a few years ago. But it has not announced any new launches since then. Tata Motors and Olectra are leading the companies trying to turn their bus fleets electric.

This does not mean that electric four-wheelers are completely missing. EV taxi services are beginning to take off. One company, BluSmart, launched its services in 2019 with 70 vehicles. It now has nearly 400 in Delhi and its satellite city Gurgaon. As the pandemic disrupted business, BluSmart started a scheme under which individuals can buy an EV and lease it to the company. BluSmart manages all operational issues, while the person who invested in the car receives a monthly assured sum. If the person does not want to continue with the programme, the company buys the vehicle from them.

“Because this business is quite capital-intensive, we have tried to make it as asset-light as possible,” says Shivam Khatter, strategy and planning manager at BluSmart.

Some other companies in Indian cities are concentrating on shared rides in e-taxis.

In anticipation of this change, new battery manufacturers are investing in plants. The first lithium-ion battery manufacturing plant, by Denso in Gujarat, will start production later in 2021. In the meanwhile, electric utility company Tata Power is among the companies developing charging infrastructure, including their deployment, maintenance and operations.

To push EVs, the state government of Andhra Pradesh has announced it will not register ICE vehicles in the new capital. The government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi is considering stopping registration of ICE taxis. Since only EV vehicles will then be registered in these areas, this will be a big boost.

There is another incentive on the cards: the government proposes to allow electric vehicles in India to be registered without batteries. Since batteries are a large part of the cost, buyers can now choose between options for battery suppliers, encouraging competition and innovation.

“We believe that the push from the government has been in the right direction and it has accelerated the electrification drive within the country. However, to maintain this momentum, it is important that the policy support and subsidies are continued to promote faster adoption, localised R&D and supply chain development,” says Girish Wagh, president of the commercial vehicle business unit at Tata Motors.

“The EV value chain itself is growing and is expected to reach USD 4.8 billion by 2025 and we are focusing on developing our own EV components, right from electric motors to battery packs and even power electronics,” Mahesh Babu of Mahindra Electric Mobility says.

If solar panels are used to charge electric vehicles in India, emissions can be cut significantly. But all of this is based on the potential of a transformation that is as yet incomplete. Some say what is needed is an iconic brand and marketing. “We need a Tesla equivalent for the two-wheeler market,” sums up Amit Bhatt of WRI India.

The Third Pole

Conversation

- Info. Dept. Reg. No. : 254/073/74

- Telephone : +977-1-5321303

- Email : [email protected]