Energy Update

Hydropower: A Bhutanese Perspective

Kathmandu; Bhutan has always cogitated hydropower as a strategic and important renewable energy resource for the country. Since Bhutan has started harnessing its hydro energy, it has enabled the country not only in achieving a notable economic growth and industrialization but also played a vital role in achieving prosperity among its people.

The hydropower sector started with the commissioning of the first mini hydropower plant in 1967. Then in 1986, the first mega hydropower plant, the 360 MW Chukha Hydropower project was commissioned, which helped raise the GDP growth rate to 25.4 percent in the following year. Then in 2006, another milestone in the power sector was achieved through construction of the 1020 MW Tala hydropower project, which again spiked the GDP growth rate to 19.7 percent in the following year, increasing the share of electricity to country’s GDP to 22 percent.

Access to cheap hydroelectricity has been considered the main driver to industrial growth and providing clean energy to the households and commercial entities alike. Rural electrification scheme has connected almost 99 percent of the households in Bhutan to the national grid, contributing to the social wellbeing of the people.

The state, by Constitution, is required to ensure that benefits accrued from natural resource are bestowed to the people of Bhutan and in line with this revenue from hydropower cascaded down to infrastructure and social development at the grassroots.

Over the last four decades, hydropower gas assumed national strategic importance and it emerged as the main driver of the Bhutanese economy. With the phased development of hydropower projects, Bhutan was able to harness 2,335 MW of power from its rivers, which has the potential to generate 36,900 MW with annual production capacity of 154,000 GWh.

In 2006, Bhutan entered into an umbrella agreement to develop 5,000 MW of additional hydropower capacity by 2020. However in 2008, the first elected government came with a grand scheme of Accelerated Hydropower Development and increased this target to 10,000 MW by 2020. The understanding is that India would help Bhutan develop these projects through bilateral and Joint Venture modality between PSU of two countries.

Therefore, Private Sector Investment was kept in abeyance. Subsequently the 1,200 MW Punatshangchhu-I, 1,020 MW Punatshangchhu-II and 720 MW Mangdechhu took off through bilateral modality. However, it invited a lot more controversies, undermining the confidence of the people in hydropower.

The trigger

The concern is whether accelerated hydropower development is too large for Bhutanese economy and has raised questions about its absorptive capacity. At a time, the three mega-projects are estimated to have doubled the country’s GDP.

Due to the sheer magnitude of the three mega projects, the impact has led to a boom in construction sector and real estate. Simultaneously, numerous economic activity has sprouted and Bhutan being an import-driven country, its foreign currency reserve took the hit. Between 2010 and 2012, the country suffered a severe INR shortage, while the government was compelled to slap import restrictions on selected commodity.

Another issue concerns with the external debt that Bhutan has been bearing. The debt to GDP ratio has started to balloon beyond 100 percent, mainly on account of hydropower projects. Although the Bhutanese government has been stressing that hydropower debts are self-liquidating, the Royal Audit Authority of Bhutan has pointed out various risk associated to repay the loans due to susceptibility to time and cost overrun. This results in revenue loss and mounting debt burden. There are also hydrological risks associated with hydropower projects.

Hydropower project in Bhutan has been mostly pursued on a bilateral model with Government of India financing the project on modality of loan and grants. In the initial Phase, 40 percent of the cost used to come in a grant, while 60 percent was loan. However, since 2008, loan component has been revised to 70 percent. At the same time, other models of execution such as Joint Venture and Public Private Partnership have also been explored.

Then came the debate of ‘putting all eggs in one basket’ and critics seemed to voice the likely occurrences of Dutch disease from hydropower. Subsequently, the focus shifted on the need to diversify Bhutan’s economic base and created employment since hydropower failed to generate local employment as anticipated.

And to nail the coffin, two mega-projects of Punatshangchhu I and II experienced geological surprises due to inadequate pre-studies. This led to cost escalation from Nu 34 billion to over Nu 96 billion accompanied by long delay in commissioning. Of the three mega-projects, only 720 MW Mangdechhu is online while Punatshangchhu II is due for 2024. Punatshangchhu-I is still in limbo with dam construction being halted due to infeasible geology.

Furthermore, there have been an increasing negative sentiments emanated from a major section of the Bhutanese on hydropower.

The New Concern

In the wake of increasing cost of building hydropower projects and huge deviation from initial estimation, power tariff of Bhutan produced electricity is bound to increase. This will impact both domestic users and importers on the Indian side.

Power tariff is determined on cost plus modality. This means all the costs incurred during the construction of hydropower include its financing costs, operation and maintenance charges, depreciation are taken into account. In addition to it, a return on equity is provisioned.

A journal published by the Center for Bhutan Studies titled ‘Export price of electricity in Bhutan,’ which has taken the case of Mangdechhu Project, pointed out that electricity should be priced at competitive rate in order to ensure comparative advantage for the economy. The study also stated that local industries, especially power intensive in nature, have already been paying higher export tariff that may barely be breakeven while a few may even run at a loss if domestic price runs high.

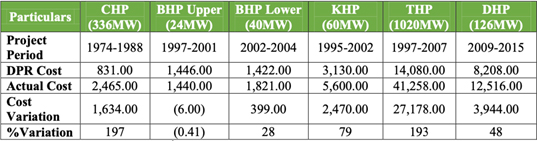

The escalation in cost of hydropower is the main concern among policy makers in Bhutan. The first mega hydropower plant, Chhukha (336 MW) suffered a cost escalation of 197 percent, an increase from Nu 831 million in 1974 to about Nu 2.5 billion in 1988. The 1,020 MW Tala has also experienced a cost escalation of 193 percent, an increase of almost of Nu 27 billion. However, tariff for these two plants are still the lowest in the region, which has given Bhutanese electricity a competitive edge in the Indian market.

On the other hand, the two projects of Punatshangchhu I and II crossed 100 percent cost overrun as of 2017. The Bhutan Electricity Authority (BEA), in its review of cost overrun for hydropower projects, has pointed out the excess cost and delays are largely on account of inflation being not considered in the initial cost estimates to get project approved, geological shocks, design changes, revision in the installed capacity and construction of additional infrastructures such as roads, hospitals and other amenities, which are in turn accounted into the tariff.

It is estimated that the final export tariff for Punatshangchhu I will hit about Nu 10. Likewise, it has been projected that total cost will increase by at least 13 million for each day of delay. Consequently, the tariff is likely to increase further.

The case in point is that as the generation cost from the Bhutanese projects increase, it will not be feasible for both India and Bhutan to invest in bigger projects.

The Prime Minister of Bhutan, Dr. Lotay Tshering, while addressing the Parliament few months ago stressed that Bhutan’s electricity tariff is increasing while the energy prices across the globe is declining.

Furthermore, Bhutan has to import power from India during the lean winter season when its generation is low and this is done through involvement in Indian power exchange. On an average, Bhutan’s export is about Rs 3 per unit and the country spends about Rs 4 a unit to import power from India.

It would be quite interesting to see how the trilateral cooperation between Bhutan, Bangladesh and India on the 1,125 MW Dorjilung Project unfolds over the time as the MoU has already been signed, while the Detailed Project Report was prepared last year.

Environmental Concerns

Bhutan’s status as the first and only carbon-negative country can also be partly attributed to its emphasis on clean, renewable energy tapped from its rivers. Aimed at encouraging developing nations to invest in greenhouse gas emission reduction projects, Bhutan has also successfully built hydro projects under the clean development mechanism, offsetting carbon emissions across the border. As a result, the 126 MW Dagachhu has started earning carbon credits.

Notwithstanding the strategic and economic importance, a quick glance into Bhutan’s own energy basket reveals that the country’s earnings from clean energy is almost negated by import of dirty energy necessitated by construction and transport sector, which are expanding year on year.

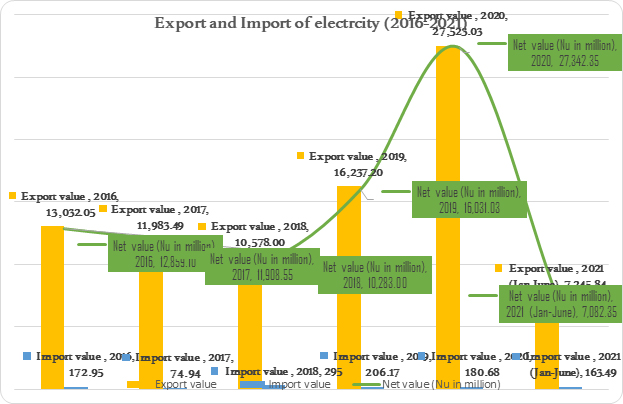

As per the Bhutan Trade Statistics, energy export to India was estimated at an average of 5,242 million units (MU) a year between 2016 and 2018, amounting to almost Nu 12 billion in total. The country also imports a small amount of electricity during lean winter months, when the river flow isn’t even sufficient to sustain domestic consumption. This leaves net earnings of about Nu 11.6 billion.

During the same period, Bhutan imported about 209 million liters of petroleum products amounting to almost Nu 10B. If the loan repayment for hydropower, amounting to about Nu 1.5 billion is put in the equation, it can be concluded that the net earnings from hydropower is traded off with import of petroleum products.

Further the construction of mega hydropower projects had drawn criticisms from conservationists, even though it was nominal. However, the unprecedented glacial meltdown is posing greater risk to hydropower projects downstream.

The New Normal

As Bhutan pursues the development of industrial estate, it is projected that the domestic demand will increase by 50 percent. In cognizance of the growing need and priority for enhancing domestic energy security, stimulating economic growth, and developing local capacity, the Druk Green Power Corporation (DGPC) was entrusted by the government to assess the potential of small hydropower projects across the country and initiated the construction of those more techno-economically viable projects.

The DGPC will begin construction of three small hydropower projects, one each at Lhuentse, Zhemgang and Haa, with a total generation capacity of 104 megawatts (MW).

What is more important for Bhutan is that, for the first time, Bhutanese companies and individuals are being involved at all layers of the hydropower project. Bhutan now has all the expertise in house- one that matches out geographical terrain, geological demands and all other factors.

The DGPC also has two other subsidiary companies- Bhutan Hydropower Service Limited and Bhutan Automation. The former is established to repair and manufacture of hydro turbine runners and associated components while the latter is instituted to deliver automation and control solutions to manage the energy systems.

As Bhutan progresses, a new focus has been shifted towards the digital economy backed by Artificial Intelligence, robotics and block chain, in addition to investing in human capacity of the country. A whole new initiative of transformation has begun in Bhutan with the objective of preparing the country for global dynamics.

The writer is a freelance journalist from Bhutan covering economy, energy and environment. He is also a co-founder of a OxMedia, a media and research firm based in Thimphu. He is a recipient of several journalism awards in Bhutan and received fellowships from UN, IMF and Royal Institute for Governance and Strategic Studies. This article taken from Urja Khabar bi-annual Journal published in 2022 Dec. 16th

Conversation

Tshering Dorji

Tshering Dorji is a freelance journalist from Bhutan covering economy, energy and environment.

- Info. Dept. Reg. No. : 254/073/74

- Telephone : +977-1-5321303

- Email : [email protected]